Nick Hull is to be congratulated for producing Jaguar Design: A Story of Style – a benchmark in authorship pulling together in sure-footed detail, the diverse strands of Jaguar design.

Contained within no less than 512 pages is a superb composite of the evolution of a brand, a marque that has stood the test of time, despite actions by various owners and even more managing directors until landing in the hands of Tata.

Titled

Jaguar Design. A Story of style this

epic covers the design story of Jaguar, from sidecars to supercars. But what is

design and what is style? The Glossary has no definition of either word.

Perhaps they are so well understood by industry’s cognoscenti that there is no

requirement for definition. But others outside this circle may appreciate

enlightenment.

Ian

Callum, Jaguar's esteemed director of design explains: "Design is about

dealing with facts….It is about creating cars that people want to buy….Good

design can be drawn in two or three lines."

But

style. What is style? Answers on a postcard please!

And

is the word style important anyhow? Tom Karen, formerly managing director of

Ogle Design, suggests: "That the design of a vehicle body is an art form

using the same language and techniques as, say, Henry Moore used to do his own

work – with a lot of added complications: legislation, the package, choice of

materials."

A distinctive appearance

Style, like design, is not

about repeating but creating something new. Style is perhaps an outward and

visible sign of inner human feelings and emotions and their expression into a

tangible form on paper, in digital form, in clay, and eventually sheet metal. Style

is also about good proportion, shape and silhouette, colour, and the optimum

expression of metal.

So when someone says: “Such

and such has style,” what do they really mean?

The

Oxford Dictionary defines style as: A

distinctive appearance, typically determined by the principles according to

which something is designed.

The

word style is probably best suited to design for the fashion industry – producing

clothes for women to make them appear smart, alluring and sexy using means that

are superficial and often not functional.

For this reason, styling applied to cars was considered by some in the

design profession as a phony, cosmetic kind of activity, far removed from ‘real’

product design where 'form follows function'.

Does

it matter if we can't define style? Perhaps it is a word everyone recognises,

but doesn't know its meaning; or doesn’t even care.

Most

who buy motor cars never see the sketches and renderings that form part of the

tortuous process of approval and counter-approval.

Don’t judge

a book by its cover

It is said that one can't

judge a book by its cover, and this book should not be judged by its cover,

which may not be the best use of art to reflect a British sports car icon and an

equally monumental book about Jaguar design and style.

The

dust jacket has design, but has it the style to reflect the pedigree of the

cars the author so admirably describes?

The

book can, however, be judged by its weight. At no less than 3075g – 3.075kg – this

detailed volume is not one to slip into the pocket! It is however a time-line

of Jaguar in design – and style – from the beginning until now. Focusing on

those responsible for design and style, it surely is a masterpiece in its own

right, ideal for those who missed, or were not able participate in the hidden

parts of Jaguar to which few gain access.

Hull

leads the reader gently but competently through the corridors of time to create

an epic testimony to Jaguar’s style, a real treasure-trove of memories.

He

also portrays how ‘styling’ has migrated from an also-ran department to mature ‘design’

status at main board level.

This

maturity in status for styling apparently grew from the appearance on the

Jaguar scene of Ian Callum. Even with 12 years at Ford and nine years at TWR

under his belt, Callum’s induction into Jaguar’s hot seat of creativity would

likely not have happened but for the untimely and premature death of chief

designer Geoff Lawson (above) on 24 June 1999, following a huge stroke.

The call he had been waiting for

Hull sheds light: “Callum got

the call he had been waiting for all his life; the chance to be Styling

Director of Jaguar.”

He

adds: “There was a feeling that Jaguar had rested on its styling laurels for

too long. So much so that the first thing Callum did was to demand the change

of the name of his position to Design Director rather than Styling Director.”

“It’s

very important that we apply some interest to what we do,” declared Callum.

So,

there it is. There is a difference between style and design. Callum’s arrival

coincided with the motor industry’s drift away from 'styling' studios to

'design' studios.

And,

in the migration of status from head of department to main board level, Callum

has for some years been one of Jaguar’s executive committee members. This

highlights the importance of design as a centre of creative activity within

business and its key role in helping to generate profit, cash and future

product flow. Design can play a part in shaping businesses to win trade. Today,

it has an equal to engineering, manufacturing, purchasing and finance.

Was

the Blackpool-born and “undemonstrative” William Lyons, Jaguar's founder, a

designer? Or a stylist? Or neither? He certainly knew what was required in a

motor car to generate excitement sufficient enough for people to want to own

one. In his own way, without going to design college, and without probably

knowing the definition of either design or style, he could create a vehicle with

form and function.

The

big business change for Sir William Lyons occurred on 6th July 1966 when he

agreed a takeover of Jaguar Cars by British Motor Corporation (BMC). The

announcement came on 11th July 1966. (British Motor Holdings – BMH – had been

known as BMC until 14 December 1966.) Thirteen months later, under Labour

government pressure, BMH merged with Lord Stokes’ Leyland Motor Corporation.

References

to Lyons abound, as do those to one of Jaguar’s biggest losses – Geoff Lawson.

Lawson’s legacy, surely, was the £6.3 million Advanced Styling Studio that he largely

initiated and ironically was signed off on 25th June 1999 – the day

following his death – and from which evolved a new “design language”.

Varying degrees of success

From its very outset Jaguar

has ploughed a single furrow, but not without several senior executives playing

their part, with varying degrees of success. Some escape with little exposure,

though one suspects they exerted a controlling influence on the levers of power

that affected styling and prototype production.

One

such escapee must surely be Geoffrey Robinson (with his convoluted dealings

with the Italians); others include John Barber, Lord Stokes, Sir Michael

Edwardes and Ford’s Bill Hayden who took over from John Egan, one of Jaguar’s

most successful bosses.

Hull

gives such men little space, with the exception of Egan, of course. It is not a

book about Jaguar management. Instead he sheds light in dark corners where

light has seldom fallen before in such profusion, namely those who have

designed (or is it styled?) well-known Jaguar cars – from C-type, D-type, through

E1A and E-type, to F-type and F-TYPE. Included are Jaguar’s cars with experimental

numbers (XJ1 to XJ220B), Daimler’s codes (XDM1 to XDM61) and X codes under Ford

– X100 to X760. XJ80 pictured above.

Owners

too along the way have poked their fingers into its affairs and generally messed

it about: British Motor Corporation, British Motor Holdings and British Leyland

Motor Corporation, with Ford Motor Company being most notable. Of all the

owners thus far, Tata seemingly is by far the most sympathetic to Jaguar’s cause.

Revealed

too are prototype shops, their task one of tirelessly and endlessly, without

glamour, glory and ceremony, transforming style and, sometimes impossible profiles,

into complex sheet metal parts (without cracks) and finally into finished

product.

Given

recognition are Abbey Panels, Motor Panels – but not Mayflower Corporation (or

Airflow Streamlines) – Park Sheet Metal, Pressed Steel/Pressed Steel Fisher and

Venture Pressings Ltd (VPL), a curious venture of Jaguar and GKN that failed.

VPL

played a key part in the life of the XJS. It started life in May 1991 as the

first major programme Ford Motor Company approved following its acquisition of

Jaguar.

A Jaguar-discarded business

In late 1994, Jaguar and GKN

disposed of VPL to Ogihara Corporation of Japan, a pressings supplier in the

mid-1990s to Ford; however, the writing was writ large on the wall in mid-1993.

Negotiations were handled by Jaguar director Mike Beasley.

So,

the Jaguar-discarded Telford-based VPL became known as Ogihara Europe Ltd.,

only later to be acquired by Stadco which, with Polynorm, had managed Jaguar’s

new Castle Bromwich press shop containing Schuler press lines that for the

first time heralded the arrival of aluminium bodysides and other pressings.

In

a further twist, Stadco purchased for a snip the newly-built gem of a press

shop at Fort Parkway (right next door to Castle Bromwich) built by Mayflower

Corporation. This can stamp steel and aluminium bodysides using almost

identical press lines to those at Castle Bromwich. Those press lines now stamp some

panels for Jaguar sports cars.

Mayflower’s

directors had the foresight to see Jaguar – and others – would need more press

shop capacity than Castle Bromwich, etc. could supply. Mayflower took the risk

and failed (through poor management) before Jaguar’s further expansion into

aluminium materialised.

Only

Hull knows if he has done a good job, but one suspects he is proud of the end

product; only he knows of any microscopic faults.

Certainly,

any author would be happy to attach his name to this epic which is certain to

stand the test of time as a record of who did what, where, when, why and how in

Jaguar design.

People like Mercs but love Jaguars

It is a book for those who love Jaguars and all that the marque stands for in the annals of automotive design.

As

much as anything it is an encapsulation of unsung heroes; stylists who carve their

future in clay; sheet metal companies who carve their future in formable

materials – groups who seldom if ever hit the headlines because of the secret

nature of their work.

With

many illustrations that readers will not have seen before, Hull brilliantly

opens the cupboard to show what did happen – and what didn't. It is certainly

the book you might wish to leave on a coffee table; that might spark a discussion

about design, and style! And whether the jacket has design and style.

Several

car designs inevitably mark turning points for Jaguar. The company's designers

will have their own recollection of what these might be.

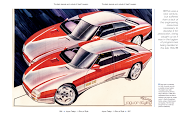

One

design stands out for this reviewer; X600, a car that could have been ahead of

its time, but never appeared as intended, marked the parting of the ways.

Hull

explains: “The car was planned to have an aluminium structure similar to that

of the X350, and considerable resources were put into the project, with over

100 engineers employed on the programme during 2001.”

X600

– fundamentally flawed

Here Hull takes in comments

from Callum: “The X600 F-type represented the last manifestation of the retro

soft-surface sports-car theme that, while it pleased Jaguar sentimentalists,

was increasingly out of step with shifting design tastes. This was an exciting

and promising proposal yet again to establish a Jag two-seater – the name clearly

signalled its intention.”

Still

referring to X600, Hull continues with Callum: “But although it caught the

imagination of many, including Ford boss Jac Nasser and design boss J Mays, who

both loved the car, the design was fundamentally flawed. It worried me at the

unveiling, because I knew that by the time it had gone through all its legal

and feasibility requirements it could look quite ordinary.”

More

Callum: “We continued with the design to make it feasible but the required

windscreen height and legal bonnet height took so much away from the exciting

proportions. At this point I instigated the idea of a mid-engine car…which

developed to a significant level of design and engineering before it was

dropped so the company could pay for some new diesel engines. From a business

point of view (it was) the right thing to do, but it broke my heart.”

Added

Callum: “Ford was in deep trouble at those times. It was struggling to reverse

losses in its core North American operations and CEO Jac Nasser was ousted in

October 2001 as a result of dissatisfaction with his leadership. Nasser’s

tenure was also marred by a scandal over deadly accidents involving Ford

Explorer sport-utility vehicles and the defective Firestone tyres with which

they were fitted.”

“Subsequently,

Jaguar chairman Wolfgang Reitzle (of BMW) also resigned in early 2002 in the

light of severe cut-backs at PAG (Premier Automotive Group to which Jaguar

belonged with Aston Martin and Volvo). The X600 F-Type was cancelled and the

Jaguar F1 operation was wound up.”

“Mark

Fields became chairman, then Lewis Booth took over in 2005, running PAG and

Ford Overseas Operations until the sale of Jaguar to Tata in 2008”.

In

these few paragraphs are found key words that over-arch car design – and

styling – namely, shifting design tastes, business, legal, feasibility,

proportion and heart.

Celebrating 75

years of Jaguar

Of course, X600 work was not

entirely wasted. In 2009, a year into Tata’s ownership, the idea blossomed of

celebrating 75 years of Jaguar and with it the concept of the C-X75 supercar.

“Of

course, we always wanted to do a supercar,” claims Callum. “But were conscious

that any extreme performance would need to include sustainable technology.”

Interestingly,

he adds, we “discovered our research

department was working with turbine technology as potential generators and

decided this would be a perfect opportunity to do something different.”

And

so began Jaguar’s work with Bladon Jets, also of Coventry, to develop a micro

gas turbine engine for C-X75. Tata’s boss, Ratan Tata, even opened Bladon Jets’

new facilities. Since then, not much has been heard of the micro gas turbine

company which describes itself as a world leader in these machines, now

promoted for power generation use. Dr. Ralph Speth of Jaguar Land Rover is

shown as a director.

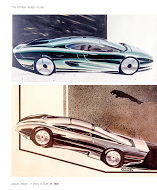

Just

as the XJ-220 (above), and its links with Jim Randle, was built in collaboration with

TWR, so for C-X75 Jaguar turned to another motorsport icon – Williams Advanced

Engineering. From that collaboration spun out the eventual announcement in 2011

that 250 of this carbon fibre car would be built for sale.

A

year after C-X75 a further advanced concept arrived, the C-X16, effectively a

reworked ‘teaser’ preview of the exciting new F-TYPE compact sports car that

the main studio had been working on for two years “using a new aluminium

construction and which was one of the first projects given the go-ahead by

Ratan Tata once he had gained control of Jaguar in 2008.” A faint hark-back to

X600 and all that.

Anyone

interested in car design, and even car styling, will benefit from immersing

themselves in this thought-provoking and immensely enjoyable treasure-rove by

Hull who claims 25 years’ experience as a designer, writer and academic on

automotive design, having worked at Jaguar on XJ41, XJ220 and XJS facelift,

Honda, Peugeot and TWR where he was involved in “bringing the Jaguar XJ220 into

production”.

Jaguar Design – a Story of Style. People –

Process – Projects. By Nick

Hull is published by Porter Press International, price £90 (US price: $169.95).

See porterpress.co.uk

No comments:

Post a Comment